Rust — your nontechnical friends and family will probably think this is all you deal with in your work in the corrosion industry. But we all know our work involves much more than this. This series of short articles—in honour of NACE International’s 75th Anniversary—attempts to paint a more positive and optimistic picture of the corrosion profession by looking at examples of successful resistance to the ravages of corrosion from around the world (and beyond) and from the distant past as well as present. It is designed to show that our chosen field is as interesting, historic, and artistic as any other.

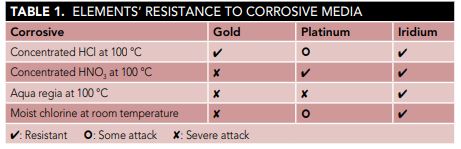

Let’s start at the beginning. We know that corrosion is a reaction between a material and its environment, so why not have a look at the most corrosion resistant metal in the periodic table. According to ASM International’s Metals Handbook1 and numerous other sources, that superlative honour goes to one of the rarest elements, iridium. It is resistant to alkalis and acids, including boiling aqua regia (a mixture of nitric acid [HNO3 ] and hydrochloric acid [HCl]), as shown in Table 1. The only substances that will dissolve the metal are molten sodium cyanide (NaCN) and potassium cyanide (KCN).

Iridium is a hard, brittle member of the so-called platinum group of metals in the periodic table. It is only a fraction less dense than the densest element, its neighbour osmium in the periodic table, and approximately double the density of lead. Iridium was discovered by Yorkshire chemist Smithson Tennant (1761-1813) in 1803, by separating and analysing the residue left after dissolving impure platinum in aqua regia. It was named after Iris, the goddess of the rainbow, because its salts were so colourful.

World production of iridium is small, only a few metric tons (tonnes) per year, and it is one of the least abundant and most expensive metals. It is produced as a by-product of nickel smelting and has few applications as a pure metal. In a pure form, it is used for electrodes in high-performance spark plugs and crucibles for the preparation of single crystals of certain electronic and optical glasses. As an alloying element, it increases the corrosion resistance of titanium and palladium, and the strength, hardness, and corrosion resistance of platinum. Despite its corrosion resistance, you are most likely to come across iridium indirectly. It is one of the mixed metals in mixed metal oxide coated titanium anodes for impressed current cathodic protection. Those involved in non-destructive testing may come across iridium192 as an isotope in radiography. There are two interesting facts regarding iridium not related to corrosion properties. One is that the last remaining base unit still defined by an artefact rather than a fundamental constant of nature is the kilogram, which is a cylinder of platinum with 10% iridium kept under nested bell jars at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures near Paris, France. The iridium is added to increase the hardness to resist wear during cleaning. It is expected that a new definition of the kilogram based on fundamental physical constants will be adopted within the next year or two.

Second, iridium is probably best known because of its association with the likely cause of extinction of the dinosaurs. The rocks in the boundary layer between the Cretaceous and Tertiary geological periods, laid down ~65 million years ago, contain a higher proportion of this element than other rocks. An iridium-enriched meteor is believed to have hit Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, and dust from the impact caused darkening of the skies that wiped out most large animals. Our next tale on successes in resisting corrosion is about metals arriving from outer space, which will be covered in the April 2018 issue of MP.S

Reference 1

J.R. Davis, ed., Metals Handbook Desk Edition, 2nd Edition (Materials Park, OH: ASM International, 1998).